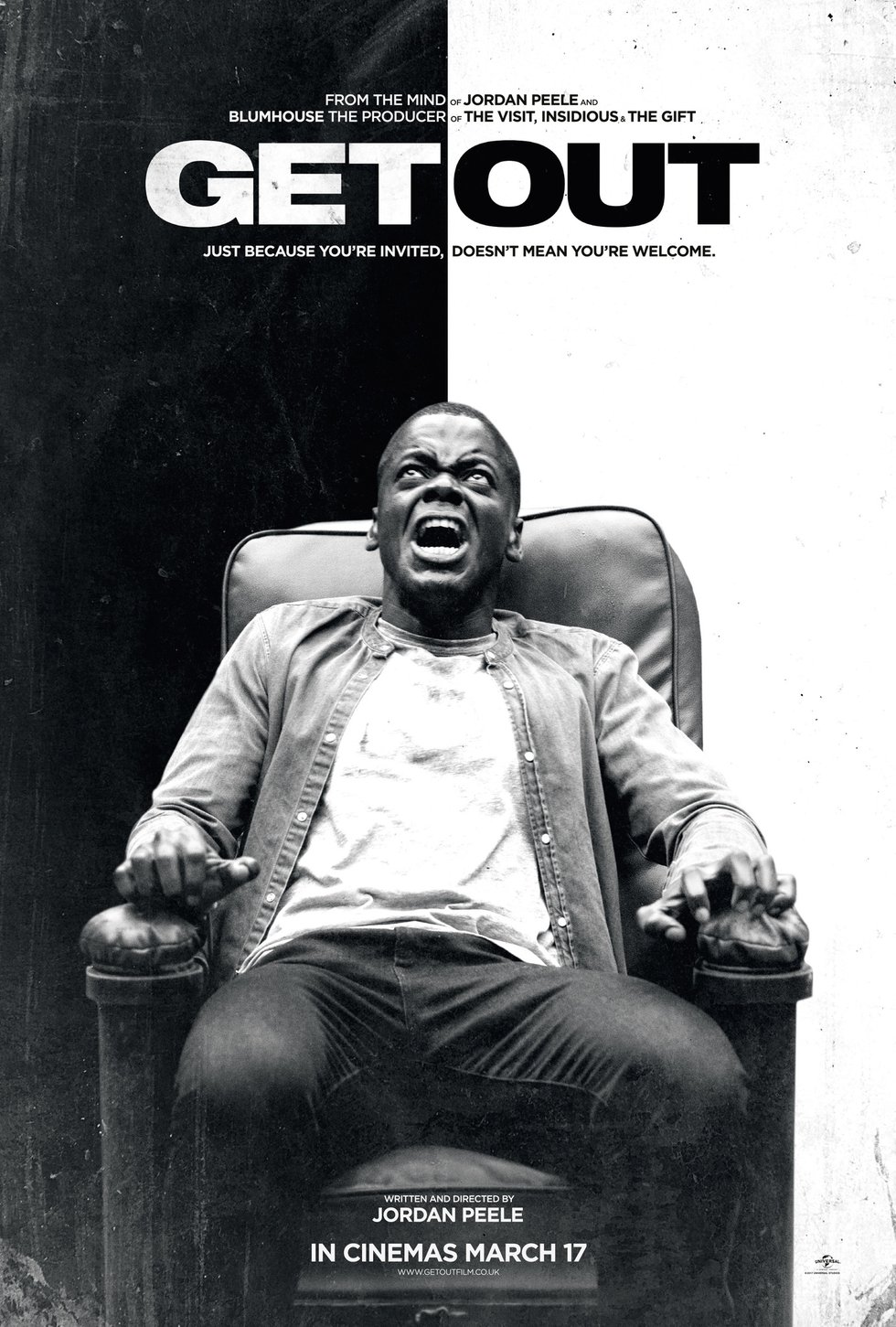

Get Out was one of the biggest successes of 2017. With a budget of $4.5 million, the film grossed over $200 million worldwide, won director/screenwriter Jordan Peele an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and became one of the most influential films of the decade. Get Out deftly weaves various genres, but settling on one has caused mild controversy, as when it was nominated for Best Musical or Comedy at the 2018 Golden Globes, Peele disagreed and stated, “…it [Get Out] was a social thriller.” However, I feel that Get Out’s genre is undoubtedly horror due to one key factor—the character of Rose Armitage and how she uses her race as a weapon.

Get Out follows the story of Chris Washington, a twenty-six-year-old aspiring photographer. He is in a relationship with Rose, a WASP-y but seemingly woke white women of a similar age. One weekend, Rose invites Chris to meet her parents at their remote country home—“Do your parents know I'm Black?” Chris asks awkwardly. “No,” Rose lies. “Should they?”

Indeed they should—it is later revealed that Rose becomes romantically involved specifically with Black men (and sometimes women) in order to take them to her father, a neurosurgeon so that he can transplant the brains of his (mainly white) friends and family into their bodies, as Black skin is deemed more desirable.

Throughout the film, we see Rose using her race as a way to ensnare and manipulate Chris. Firstly, we see Rose using her white privilege as a way to trap Chris. In the film’s first act, Chris and Rose encounter a police officer on their way to her parent’s house. The officer asks to see Chris’s license (even though he wasn’t driving the car) and Rose calls the officer out on his 'bullshit.'

However, what initially appears to be Rose standing up against institutionalized racism in the police force is chilling in hindsight; she was doing it so that Chris’ details were not recorded for when he later goes missing. The fact that she was able to do this was due to her white privilege—Chris, a Black man, alone, would not able to convince the officer to let him go otherwise.

Another way in which Rose uses her white skin to her advantage is by falsely displaying herself as an ally. On their first night at her parent’s house, Rose rants about her parent’s apparent lack of cultural awareness around Chris, sounding even more appalled than he does, who experiences it firsthand. On the DVD commentary, Jordan Peele said that “I think the scene is pivotal in our not suspecting her… the fact that she’s more turned up about this than he is.”

Later, in the scene where Chris decides to stay at the Armitage’s home because of his love of Rose, she deceives him further by suggesting that they should in fact leave. Rose’s deception is revealed in a killing blow at the end of Act II, where she iconically reveals that she has Chris’ car keys, preventing him from leaving and exposing her part in the plan.

Chris is then physically restrained by Rose’s brother and put into the 'sunken place' by Rose’s mother. However, the unique thing about Rose’s villainous reveal was not the fact that she was a ‘bad guy’, but the way it was executed.

Instead of telling Chris that she despised him or was revolted by them being together, she calmly says, ‘You were one of my favorites’ as if consoling him. It’s not just a shocking plot twist, it’s an emotional gut punch.

For The Guardian, journalist Lanre Bakare writes: “The villains here aren’t southern rednecks or neo-Nazi skinheads, or the so-called 'alt-right.' They’re middle-class white liberals… It [Get Out] exposes a liberal ignorance and hubris that has been allowed to fester. It’s an attitude, an arrogance which in the film leads to a horrific final solution, but in reality, leads to a complacency that is just as dangerous.”

And that ‘complacency’ is just what makes Rose so horrifying—she is just as racist as a so-called ‘neo-Nazi skinhead,' but she doesn’t realize this because of her so-called liberal ideals. The Armitage family wants Black bodies not to erase them but to inhabit them for their more admirable traits. In a weird way, Rose doesn’t see herself as racist—she thinks she’s paying him a compliment by having chosen him in the first place.

This attitude is a deliberate reflection by Jordan Peele on contemporary America. In the aftermath of Trump winning the 2016 election against Hillary Clinton, widespread marches erupted across America (and the world) which focused on Trump’s history of sexual assault and misconduct.

However, the marches at large failed to address the fact that 53% of white American women voted for Trump, a shocking comparison to the 94% of Black women who voted for Clinton. White women contributed greatly to Trump being elected, but the white women who went on the marches against Trump only considered the effect on their rights and not the additional impact on the rights of Black women and women of color.

Another way in which Rose uses her white privilege as a source of horror was in her phone conversation with Chris’ friend Rod. He was concerned and suspicious of Chris’ sudden disappearance and was enquiring about his whereabouts. Rose initially acts innocent and tries to draw sympathy from Rod, saying she’s ‘so confused’ by the situation.

However, when Rod doesn't fall for Rose’s ploy, she changes tactics; she states that the reason Rod called was because of his alleged sexual attraction to her, asserting that she knows ‘you [Rod] think about fucking me.’ Rod hastily hangs up, adding that Rose is a ‘genius.’ And Rod is telling the truth; Rose is not only weaponizing her whiteness but her white femininity.

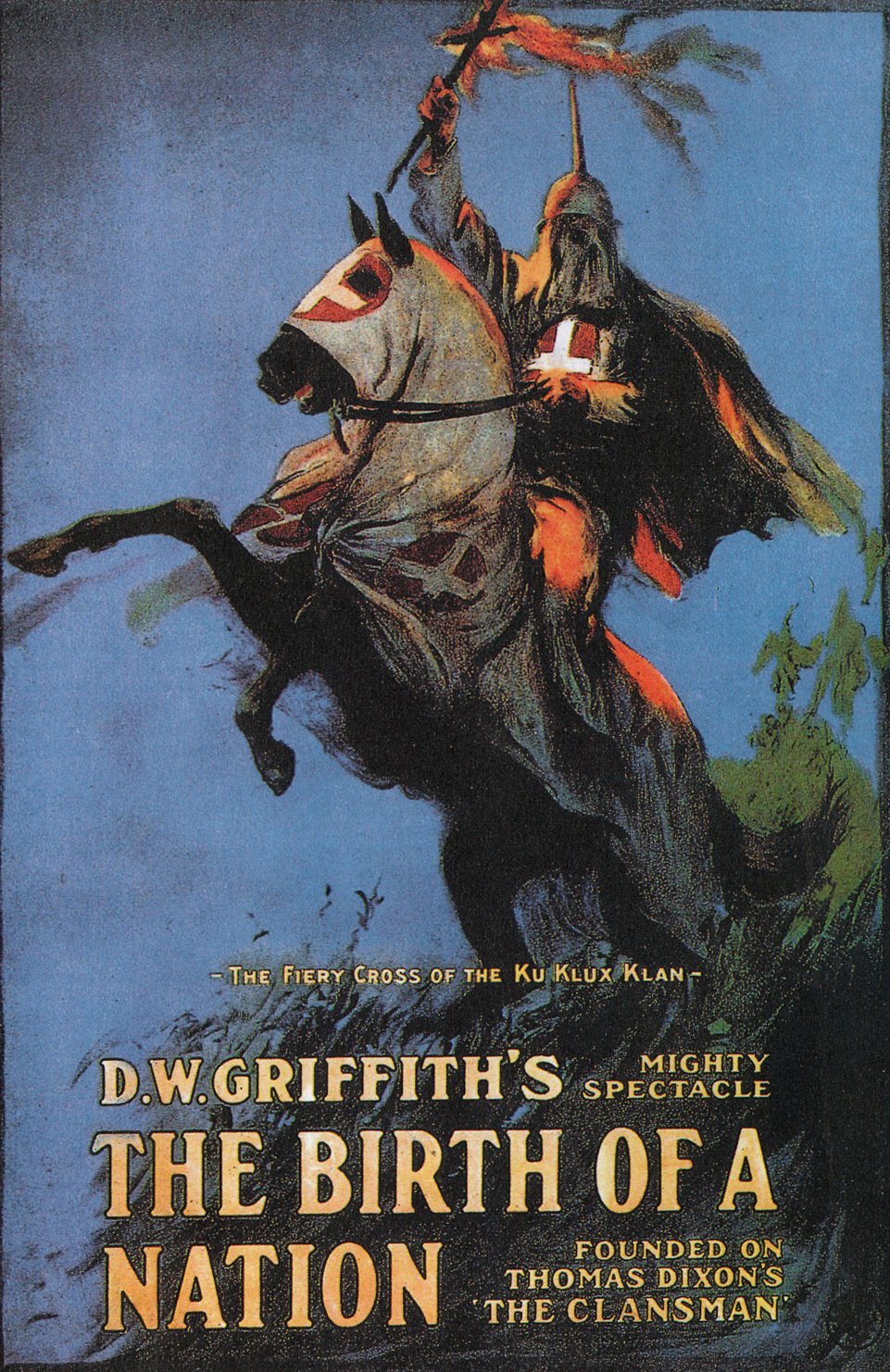

The fear of Black men attacking white women has been ingrained in the American subconscious for over a century. The film The Birth of A Nation helped to create this fear—in Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th, writer/educator Jelani Cobb notes: “There’s a famous scene where a woman throws herself off a cliff rather than be raped by a black male criminal. In the film you see black people being a threat to white women.” Despite this, The Birth of A Nation was (and still is) considered to be one of the greatest films of all time, and until recently was still being taught in film schools across America.

The idea of Black men being a threat to white women was still being peddled by American society well into the 21st century, with one of the recent prominent examples being the Bush vs. Dukakis presidential election in 2003. Dukakis wanted criminals to have weekend releases and to combat this, Bush’s campaign used Willie Horton, a Black man convicted of raping a white woman as a fear-mongering tactic against Dukakis.

Again in 13th, Harvard professor Khalil G. Muhammed states: “Bush won the election by creating fear around black men as criminal, without saying that's what he was doing... It went to a primitive fear, a primitive American fear because Willie Horton was metaphorically the black male rapist that had been a staple of the white imagination since the time just after slavery.”

Rose not only uses this American fear against Rod but also against Chris. In the film’s final act, Chris manages to escape the Armitage home and the fate of all of Rose’s previous exes. Rose pursues him with a shotgun but is ultimately mortally injured by Walter, a Black gardener whose mind was occupied by Rose’s grandfather.

As Rose lays on the road dying, Chris goes to her and begins to strangle her. He cannot bring himself to finish the job, however, but it doesn’t matter—flashing lights fill the screen, and Rose, thinking it’s the police, theatrically cries for help.

In the theatrical ending, it turns out to be Rod coming to Chris’ rescue, not the police coming to Rose’s, much to the audience's delight. However, Jordan Peele originally had a much bleaker idea in mind and shot an alternate ending, one that did indeed have the police arriving and Chris ultimately put in prison.

In the podcast Another Round, Peele notes that “The ending in that era was meant to say, ‘Look, you think race isn’t an issue?’ Well, in the end, we all know how this movie would end right here.” And it’s true, hence why Rose immediately started to cry for help when she saw the lights.

Although a fictional film, we know that the image of Chris, a Black man, crouching over a wounded white woman, would’ve been a life sentence for the character. Even though she would’ve died in both endings, Rose could’ve still won in the alternate ending due to her race.

Catherine Keener’s character Missy Armitage also uses her whiteness as horror in Get Out. In the aforementioned podcast, Peele explains, “The idea of getting hypnotized or being in a psychiatrist’s chair which is partially playing off of the stereotype and generalization that the Black community hasn’t exactly embraced therapy as a means to get to your inner turmoil…religion is where it goes.” Missy’s character using a therapeutic technique to manipulate Chris was a deliberate ploy by Peeleto to create anxiety in the Black audience and more specifically have that anxiety being sourced by a white character.

Even though the other two members of the Armitage family, Dean and Jeremy, can physically antagonize Chris—Dean, the father, would be the one to perform the operation on Chris and Jeremy, the son, is his physical opponent,—neither affect Chris’ psychology or character development in the way that Missy and Rose do.

In John Truby’s novel The Anatomy of Story, the writer proposes, “Create an opponent… who is exceptionally good at attacking your hero’s weaknesses.” Both Missy and Rose do exactly this—Missy introduces a weakness of Chris, the fact that he left his mother to die, and brings it to the fore. This leads Chris to decide to stay with Rose later in the movie, as he tries to right the wrongs he made in the past for her. Missy exposed Chris’ weakness and Rose exploited it. The actions of the two women are what help drive the narrative forward.

Another way in which Peele made Rose a source of horror in Get Out was altering the ‘final girl' trope. Like most final girls, Rose is white, young, intelligent, and spends the majority of the film in an isolated house. However, instead of being the one to escape the monster and live to tell the tale, she is the monster and is ultimately the one who is defeated by the film’s true hero.

Furthermore, in their video essay on ‘Final Girls’, The Take surmises, "The flip side to the ‘final girl’ after all is the ‘black guy dies first’ trope. While audiences are expected to be terrified for the white girl, the deaths of black characters are regarded as just part of the show.” The fact that Rose is the film's baddie is subversive, but the way that Peele wrote for Chris, a Black man, to be the one to defeat her, is a delicious spin on audience expectations of the horror genre.

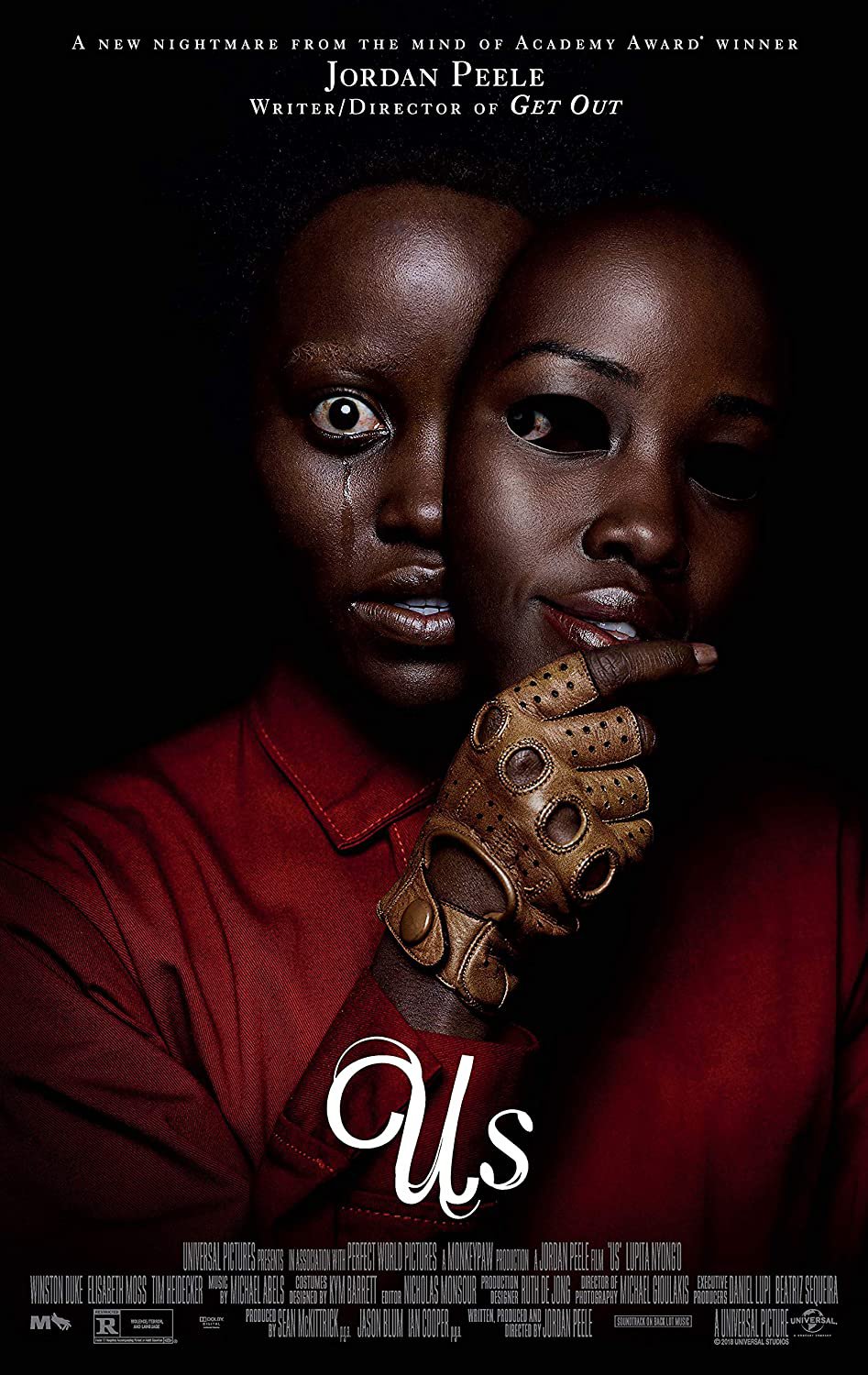

This new take on the 'Final Girl’ seems to have ushered in a new generation of women in horror—since Get Out’s 2017 release, we have since seen Suspiria, Midsommar, and Us (also by Peele), where the final girls are either the villains or go to dark lengths in order to achieve their goals. Final girls are no longer enduring horror—they are inflicting it.

Rose Armitage is one of the scariest on-screen villains in recent years, but not because she has fangs or wields a chainsaw—it is because we know someone like a Rose in real life. Rose is the most dangerous character in Get Out because she is the most real. Even though her malevolence is overwhelming, Jordan Peele does not want audiences to cower from her, but rather face her head-on.

Get your copy of the Get Out 4K Blu-ray by clicking here.

Get your copy of the Birth of a Nation DVD by clicking here.

If you want to learn more about race and the film, order the book Critical Race Theory and Jordan Peele's Get Out.